|

| ©Darpa |

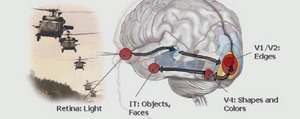

| Darpa says a soldier's brain can be monitored in real time, with an EEG picking up "neural signatures" that indicate target detection. |

U.S. Special Forces may soon have a strange and powerful new weapon in their arsenal: a pair of high-tech binoculars 10 times more powerful than anything available today, augmented by an alerting system that literally taps the wearer's prefrontal cortex to warn of furtive threats detected by the soldier's subconscious.

In a new effort dubbed "Luke's Binoculars" -- after the high-tech binoculars Luke Skywalker uses in Star Wars -- the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is setting out to create its own version of this science-fiction hardware. And while the Pentagon's R&D arm often focuses on technologies 20 years out, this new effort is dramatically different -- Darpa says it expects to have prototypes in the hands of soldiers in three years.

The agency claims no scientific breakthrough is needed on the project -- formally called the Cognitive Technology Threat Warning System. Instead, Darpa hopes to integrate technologies that have been simmering in laboratories for years, ranging from flat-field, wide-angle optics, to the use of advanced electroencephalograms, or EEGs, to rapidly recognize brainwave signatures.

In March, Darpa held a meeting in Arlington, Virginia, for scientists and defense contractors who might participate in the project. According to the presentations from the meeting, the agency wants the binoculars to have a range of 1,000 to 10,000 meters, compared to the current generation, which can see out only 300 to 1,000 meters. Darpa also wants the binoculars to provide a 120-degree field of view and be able to spot moving vehicles as far as 10 kilometers away.

The most far-reaching component of the binocs has nothing to do with the optics: it's Darpa's aspirations to integrate EEG electrodes that monitor the wearer's neural signals, cueing soldiers to recognize targets faster than the unaided brain could on its own. The idea is that EEG can spot "neural signatures" for target detection before the conscious mind becomes aware of a potential threat or target.

Darpa's ambitions are grounded in solid research, says Dennis McBride, president of the Potomac Institute and an expert in the field. "This is all about target recognition and pattern recognition," says McBride, who previously worked for the Navy as an experimental psychologist and has consulted for Darpa. "It turns out that humans in particular have evolved over these many millions of years with a prominent prefrontal cortex."

That prefrontal cortex, he explains, allows the brain to pick up patterns quickly, but it also exercises a powerful impulse control, inhibiting false alarms. EEG would essentially allow the binoculars to bypass this inhibitory reaction and signal the wearer to a potential threat. In other words, like Spiderman's "spider sense," a soldier could be alerted to danger that his or her brain had sensed, but not yet had time to process.

That said, researchers are circumspect about plans to deploy the technology. One participant in last month's Darpa workshop, John Murray, a scientist at SRI International, says he thought the technology was feasible "in a demonstration environment," but fielding it is another matter.

"In recent years the ability to measure neural signals and to analyze them quickly has advanced significantly," says Murray, whose own work focuses on human effectiveness. "Typically in these situations, there are a whole lot of other issues (involved) in building and deploying, beyond the research."

It's unclear what the final system will look like. The agency's presentations show soldiers operating with EEG sensors attached helmet-style to their heads. Although the electrodes might initially seem ungainly, McBride says that the EEG technology is becoming smaller and less obtrusive. "It's easier and easier," he says.

But getting the system down to a target weight of less than five pounds will be a challenge, and Darpa's presentations make it clear that size and power are also issues. But even if EEG doesn't make it into the initial binoculars, researchers involved in other areas say there are plenty of improvements to existing technology that can be fielded.

For example, another key aspect of the binoculars will detect threats using neuromorphic engineering, the science of using hardware and software to mimic biological systems. Paul Hasler, a Georgia Institute of Technology professor who specializes in this area and attended the Darpa workshop, describes, for example, an effort to use neural computation to "emulate the brain's visual cortex" -- creating sensors that, like the brain, can scan across a wide field of view and "figure out what's interesting to look at."

While some engineers are mimicking the brain, others are going after the eye. Vladimir Brojavic, a former Carnegie Mellon University professor, specializes in a technology that replicates the function of the human retina to allow cameras to see in shadows and poor illumination. He attended last month's workshop, but he said he was unsure whether his company, Intrigue Technologies, would bid for work on the project. "I'm hesitant to pick it up, in case it would distract us from our product development," he says.

According to the Darpa presentations, the first prototypes of Luke's Binoculars could be in soldiers' hands within three years. That's an ambitious schedule, and an unusual one for Darpa, note several workshop attendees, who also say they expect fierce competition over the project. The list of attendees at the meeting ranged from university professors to major contractors. Spokespeople for Lockheed Martin and Raytheon both confirmed interest in the program, but declined to say whether they would bid on it.

Once fielded, Darpa indicates the measure of success lies with the military. According to information the agency provided to industry, initial prototypes would go to Special Forces. If the military asks to keep the binoculars after the trials, "that's exactly what you want here," Darpa wrote. "That's success."

Why all the rush? "I have to wonder if they aren't under pressure from Congress to make a contribution (to the war on terrorism), or if DOD is really leaning on them to come up with some stuff," suggests Jonathan Moreno, a professor of ethics at the University of Pennsylvania, whose recent book, Mind Wars, looks at the Pentagon's burgeoning interest in neuroscience. Darpa did not respond to press inquiries about the program.

Despite the fast schedule, McBride, of the Potomac Institute, thinks the idea is doable. "It's a risky venture, but that's what Darpa does," he says. "It's absolutely feasible."

This way, Only few psychopathic machines can control what is happening in the battlefield at soldier level. Looks like Pathocrats doesn't even have confidence in their mind control technology , so they have to create this type of crap.